Design, Ecology, Politics: Toward the Ecocene has been reviewed three times:

- Eye Magazine, by John-Patrick Hartnett with various designers.

- The Design Journal by Paul Micklethwaite.

- Communication Design Quarterly, by Ryan Cheek

Design, Ecology, Politics: Toward the Ecocene has been reviewed three times:

Written with Alistair Alexander for presentation at After AI Symposium (17 May 2024)

AI can be seen as the ultimate and most extreme manifestation of extractive technological accelerationism. The rapid development of AI infrastructure to meet the exponential scaling of Large Language Models is already causing power shortages in the US energy grid (Halper 2024). Key figures in AI claim that its astronomical power demands will require a future energy “breakthrough” (Reuters 2024). According to Scientific American, large-scale energy from nuclear fusion is not likely to materialise “before around 2050 (the cautious might add on another decade)” (Ball 2024). Meanwhile, the resource inputs for manufacture of the specialised AI GPU processors are not disclosed by manufacturers, but they are also necessarily prodigious. The dynamics of industry hype, speculation, and financialisation exist independently of the material requirements and ecological consequences of AI technologies.

In this presentation we offer strategies to assess AI’s ecological and social impact – both positive and negative – beyond the current hype cycle. We present ecological frameworks to help to methodically assess the true potential of AI – or lack thereof – in a context of climate and ecological crises and (our hoped for) capacity for planetary regeneration. Like all technology, AI depends on natural resources and relatively stable ecological circumstances. We use the concept of “after” as part of a long series of post-bubble and post-collapse states where aspirations and promises of AI hit boundaries of resource requirements to manufacture AI, the energy to power AI, and the ecological consequences of these processes, including associated acceleration of GHG emissions, and associated climate change impacts. Intersecting vectors of ecological, social, and economic crises will all be accelerated with incautious approaches to AI where the supposed “unintended consequences” have yet to be accounted for in the new proposals. In this context, the speculation that widespread AGI can exist in the context of the polycrisis is pure fiction. The fact that the tech world has made this narrative as dominant as it is, reveals a deep denial and dismissal of the ecological context in tech discourses, a consequence of ecological illiteracy.

New publication – Open Access

Our Design Research Society Sustainability Special Interest Group text was just published in Brand Magazine. This is what we wrote.

1/

Despite over 50 years of calls for action on ecological concerns, the design industry has not yet enacted a substantial response to the accelerating climate and ecological emergencies. Design institutions are slowly responding with attempts to bridge the gap between current design priorities and those that will enable the design of sustainable ways of living on the planet. How can designers facilitate responsive actions on a scale that could make a difference?

Sustainability discourses in design have grown and diversified. Originally preoccupied with the remediation of industry processes and practices to drive resource efficiencies (i.e., doing more with less), the field has broadened to recognise a much wider range of ways that design theory and practice can generate ecological value and social justice. This period of history has also witnessed alarming decreases in planetary health, evidenced through the overshoot of many ecological ‘planetary boundaries’ such as a warming climate, ocean acidification, high levels of biodiversity loss and extinctions. Alongside these physical impacts are a series of cultural ones found in the under-representation of voices from people with economic, health, security, and habitat poverties.

2/

The position and power of design education and design research for sustainability in creating both strategic and practical positive impact is fractured. The definition of ‘sustainability’ is a case in point. Shifting the language and activity of sustainability from responses favouring amelioration, ecoservice logics and resource efficiencies, to one instead revealed through critical ecological and social value, proves challenging.

Misappropriation of the terms ‘sustainability’ and ‘sustainable’ further complicate ways in which new knowledge and understanding can be adequately authenticated against pervasive green-washing, techno-fix reliance and oversimplifications of complex transition imperatives. We now face a critical, ecological turn. The crux of this shift for design research is the need to redefine this discipline space in transitionary times to create the ecological imagination of, and ways for design, as this century progresses.

The distinction between rigorous approaches to sustainable transitions and greenwashing discourses is a battleground in many design institutions. Outdated priorities, ideas and structures need to be challenged. The ways of thinking and doing that led to our current crises are not fit for purpose. Yet ecologically engaged perspectives are still poorly understood by many.

Continue readingGreenwashing is normal in industries involved with unsustainable development. In my attempts to help highlight greenwashing, I have encountered resistance in the form of sexism. It seems that far too many people cannot recognise sexism when it is happening. In response to these experiences, I have made a handy graphic. Perhaps this tool will help identify it when it occurs so changes can be made.

Thanks to the people @slowfactory and @theequalityinstitute for the inspiration. Also I need to say that as a white women, I have privileges denied to the majority of people on this planet. All the dynamics described above intersect with other types of discrimination faced by people of colour and other groups who face much more severe types of structural and systemic discrimination.

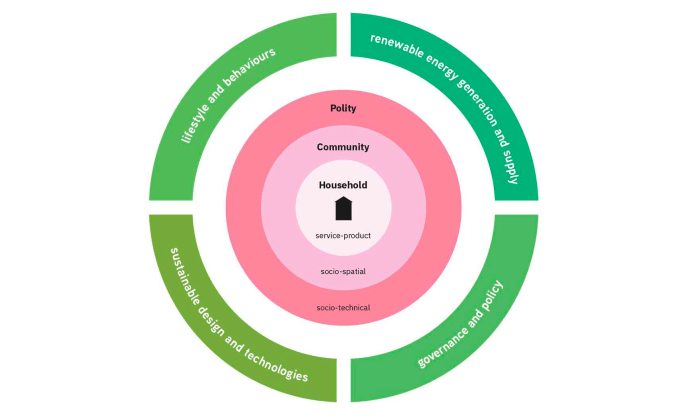

Transition Templates: Pathways to Net Zero+ is a three year research project funded by the AHRC Innovation Scholars Programme as a collaboration between Dr. Joanna Boehnert of Bath School of Design and Livework’s Sustainable Futures Lab.

The project will map pathways for Net Zero+ in five sectors of the UK economy. We bring outside academics and organisations into a collaborative space by conducting expert and stakeholder consultation and participatory systems mapping. This work will inform the development of systemic-service design processes for socio-technological transitions. For each sector, a new Transition Template design process will be applied to envision low carbon models of living.

We will work with sustainability scientists, researchers, and practitioners using systemic and service design to articulate and visualise their proposals. We will plot transition pathways on different levels with systemic mapping practices. Templates and timelines will be constructed as action plans in each sector. These will also become a basis for evaluation systems to categorise levels and stages of transition. The work will encourage best practice by creating classification systems to identify, assess, and communicate different levels and stages of sustainable transition.

We will start with household energy ecosystems. We will design accessible outcomes to inform socio-technological transformation of the entire sector across scales. We will design evaluation and assessment communication systems to counter the deleterious impact of greenwashing. With this work we will build capacities to envision, develop, and enact Net Zero proposals.

Funded by the AHRC Innovation Scholars Programme, part of UK Research and Innovation. Project Reference: AH/X005186/1.

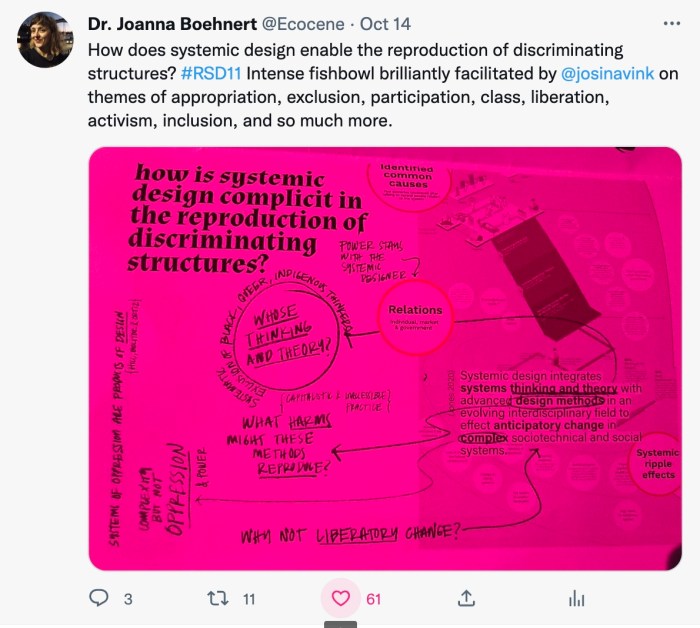

Perhaps I am biased because I did my PhD at this university, but last month’s Relating Systems Thinking and Design (RSD11) “Possibilities and Practices of Systemic Design” at the University of Brighton felt to me like the most ecologically engaged design conferences I have yet to attend. The RSD11 community are working in a wide variety of ideas and practices for systemic design. Often this work includes a focus on justice-oriented design for sustainable transitions. RSD11 included an impressive stream on confronting legacies of oppression. The systemic design research community (now formally established as the Systemic Design Association) has developed theories and practices over the last decade that are now being advocated by the UK Design Council as a design approach for Net Zero. There was so much good content I made some time to capture and share just a few moments, ideas, and reflections on key themes that I consider to be particularly relevant to current debates in design theory and education.

I will start with the Tony Fry, one of strongest voices on designing viable futures in an era of planetary crises. Fry emphasises that we must be careful about the definition of “sustainability” to build capacity to move beyond “sustaining the unsustainable” – which sadly characterises the defuturing work in much of the design industry today. Moving beyond defuturing practice will be done by “redesigning design” and depends on an expansive design practice and “informed futuring” based on critically and ecologically engaged design education.

This design education theme emerged in Fry’s keynote in response to a question by System Design Association’s board chair Silvia Barbero. The popularity of this theme is evidenced in Dan Lockton’s popular tweet (below) – and as a topic of conversation in the final panel and plenary. Judging by nearly two hundred people on Twitter alone are concerned about the capacity of design education to deliver the types of knowledge needed to meet design challenges of the futures. We discussed the narrow and instrumental focus of attention in some design schools and how this impacts our attempts to advance responsible design, design for sustainability, social design, decolonising design, etc.

On the topic of sustainability, systemic design has recently been recognised as a means of addressing climate change by the UK Design Council in the Beyond Net Zero: A Systemic Design Approach report. Numerous sessions presented strategies for redirecting designed worlds for dramatically reduced GHG emissions (including my own mini-workshop).

Design’s role in reproducing or even creating new discriminating structures and systems – or, alternatively, creating liberatory ones, was developed in the many sessions in the “Confronting Legacies of Oppression in Systemic Design” stream. Social justice oriented ideas have made impressive progress over the last five years in design theory and this was very much evident in these sessions. There was also time to consider some of the challenges this community faces now that our ideas are gaining some legitimacy in institutional spaces.

Josina Vink facilitated an intense fishbowl where tensions were discussed. One particularly troublesome issue that arose in this space and a problem that exists as real threat to both the justice-oriented design community and the sustainable design community, is the issue of appropriation.

Appropriation occurs where ideas generated in the margins of dominant discourses (often by marginalised groups) are extracted from the communities that have nurtured these ideas and practices, decontextualised, rinsed of their transformative potential, and used in ways that destroy the value of the idea or practice. Some examples of appropriation could be:

The list above is a partial list of the various ways that the appropriation of the language of justice and sustainability devalues the work of scholars and activists who leading these movements. This list describes just a few ways appropriation can happen in academic spaces. Appropriation not only delays (or wrecks) progressive movements – but it also harms individuals working (often on the margins) for social change. Appropriation was a dominant theme in the fishbowl as those who have been involved with building capacity for social change in design witness the appropriation of their work.

Also speaking to the theme of justice was Lesley-Ann Noel who described the work of moving beyond good intentions: “learning how to see oppression so we don’t reproduce it.” Noel highlighted Arturo Escobar’s version of the pluriverse in design theory and asked: “could design be guided by different design principles?” Noel presented her “positionality wheel” as a tool to prompt reflection and better understand power, agency, and relationality.

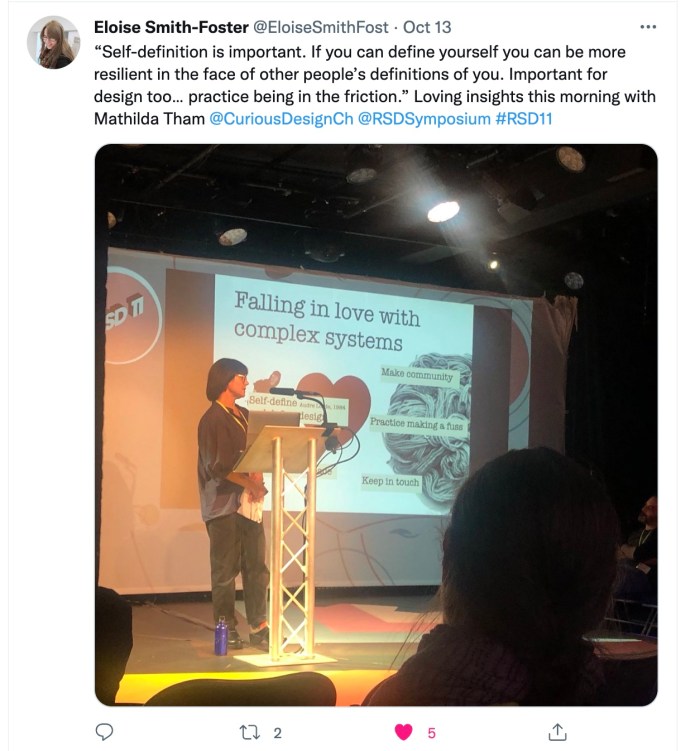

Another highlight was Mathilda Tham’s keynote, with her Earth Logic proposal, and metadesign practice. There were many helpful reflections here. The idea about the importance of self definition (see below) for feminist designers struck me as particularly helpful, and echos Noel’s ideas on positionality – especially for designers who are advocating on behalf of traditionally marginalised groups.

Danah Abdula described the contradictions of sustainability in graphic design. This keynote illustrated the various ways graphic design is so complicit with greenwashing – but also, potentially, able to help re-imagine and remake the material world. Abdula’s presentation illustrated the politics in communication design and how agency is diminished with uncritical approaches to communication design. The article Against Performative Positivity captures these themes in more detail.

Peter Stoyko presented his new Pattern Atlas that I highly recommend checking out for those interested in systems and/or illustration. There are lots of creative commons resources here that can be freely used in systems mapping and other work.

Also see Chantal Spencer’s paper on participatory research with insights on inclusive practices.

Finally, System Design Association’s Board Chair Silvia Barbero discussed the role of designers and systemic design in planetary health using the Planetary Health Framework. She played the “Nature Is Speaking” video below. I am sharing here as a good example of story telling on the environment.

For RSD11 colleagues, please forgive me but I can only capture a few moments of so much good content. This blog is very partial. I have not even made time to describe my own mini-workshops on net zero or a second one on design education. These were good too! I want to thank the whole team at the University of Brighton for hosting such a great event. Also thanks to everyone involved with building the Systemic Design Association from scratch over the last 11 years. I have learned to much from this community since I attended RSD1 is Olso – and this was probably the best conference yet. Papers and posters are on the SDA website.

Last week I presented a keynote at the Design History Society Annual 2022 Conference in Ismir Turkey on the theme of Design and Transience. My talk was called “Design History and Design Futures: Beyond Anthropocene Ontopolitics.” I used the time to consider how design history might look at design artefacts and designed systems if we were to consider all design through the lens of ecological entanglement. This is not a minor difference from the current way of thinking about design.

Design has a pivotal role to play in creating new sustainable ways of living on this planet. But changing direction in design involves moving away from some of the assumptions that are propelling unsustainable and defuturing design practice. Design is evolving in response to debates that have emerged over the past 50 years as the sciences, the social sciences, and the arts integrate ecologically engaged ways of knowing into knowledge systems that have traditionally erased the ecological. This theory can inform the dialogue between design history and design futures. Examining the assumptions embedded in ideas, priorities and value systems that inform design history, we can potentially create space for new agencies for regenerative design futures.

In response to feedback I received at the conference I am going to develop the paper by applying the theory to some historic examples of “good” design. If we apply a lens consistent with Anthropocene ontopolitics, many examples of good design will need to be re-evaluated. I am interested in your opinions readers so if you have any examples of design artefacts that should be evaluated through the lens of ecological entanglement, please feel free to comment below or message me.

I’ve uploaded “Design History and Design Futures: Beyond Anthropocene Ontopolitics” keynote for the Design History Society’s 2022 Annual Conference on Design and Transience to slideshare (link below). I’ve only included slides with quotes, along with AI images – they can be downloaded. My own words will be in the upcoming paper.

All AI generated images and slides are published as Creative Commons – Attribution and Share-alike. More images can be downloaded on Instagram here.

Five papers have just been published with our editorial from the Power and Politics in Design for Transition track at Loughborough University’s Research Perspectives In the Era of Transformations conference 19-21 June 2019.

The politics of design transitions remains marginal in design research. With our call, we hoped to receive contributions that problematised design’s current roles and conceptualised new roles for design in the context of sustainability transitions to attend to issues related to how power is and should be dealt with.

Track chairs

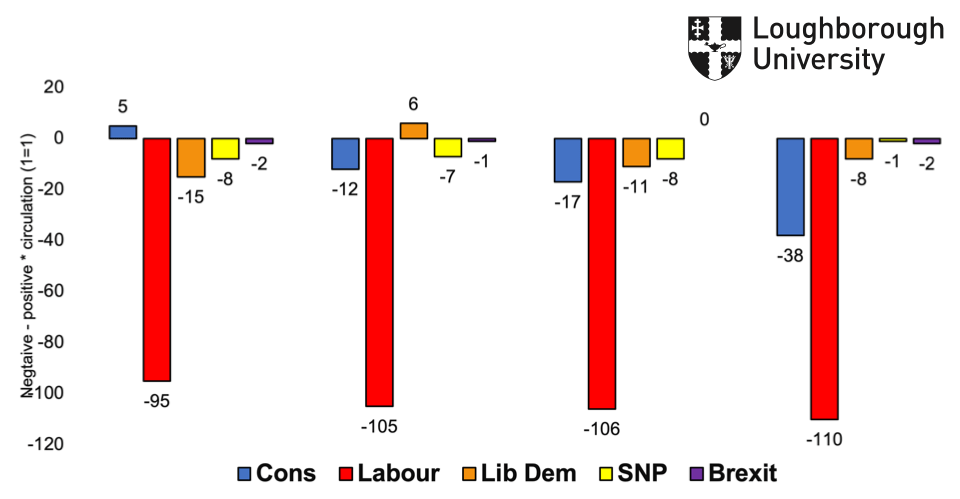

Approach media speculations about the cause Labour defeat with great skepticism. They will not own the way they have vilified the left Labour movement and destroyed this opportunity to create a fairer society and address climate change over the next decade. We did not lose because of Corbyn. We have lost this election because 40 years of neoliberalism have greatly diminished living standards for the majority, hollowed out the media and left people without access to the information and analysis they need to resist the political forces that will now take apart the NHS, sell off public services, avoid climate action, etc. Research at Loughborough university has demonstrated how negativity toward Labour in press in this election campaign outstrips all other party’s: “The overall high level of negativity towards the Labour Party has remained constant throughout the election campaign, increasing week-by-week. Manifesto and policy announcements have not managed to reverse this trend over the course of the campaign.”

There is precious little left wing mainstream media to offer effective counter analysis – as both the BBC and The Guardian have been dominated by the viciously anti-JC centre right. The Corbyn-supporting social movement that tried to resist these forces did everything we could to bring counter analysis and narratives to people’s doorsteps over the last month. It was not enough. No where was that more apparent than in South Thanet where our brilliant Labour candidate was defeated by a corrupt Conservative quietly enabling the destruction of local health services.

What could be more important than sustaining habitable living conditions on Earth? Climate change, biodiversity loss and other environmental problems demand changes on an order of magnitude well beyond the trajectory of business-as-usual. And yet, despite accumulative social and technological innovation, environmental problems are accelerating far more quickly than sustainable solutions.

The design industry is one of many industries mobilising to address environmental imperatives. While sustainability-oriented designers are working towards change from many angles, addressing climate change and other environmental problems on this scale demands much more dramatic transformations in economic ideas, structures and systems that enable – or disable – sustainable design.

Put simply, designers cannot design sustainable future ways of living on scale without a shift in economic priorities. Human impacts on planetary processes in the Anthropocene require new types of ecologically engaged design and economics if the necessary technological, social and political transitions are to take place.

Design is crucial to this debate because it is key to the creation of future ways of living. Designers make new ideas, products, services and spaces desirable to future users. With the shape of a font, a brand, the styling of a product, the look and feel of a service, the touch of a garment, the sensation of being in a particular building, designers serve the interests of customers (generally, those with disposal income). They do so according the logic and modes of governance generated by what is valued by economic structures. Design is the practice that makes capitalism so appealing. Continue reading

I am attending the EAD2019 this week in Dundee where I will present my paper “Ecocene Design Economies: Three Ecologies of Systems Transitions.” I am publishing the link to this paper here.

Ecocene Design Economies: Three Ecologies of Systems Transitions

Despite accumulative social and technological innovation, the design industry continues to face significant obstacles when addressing issues of sustainability. Climate change and other systemic ecological problems demands shifts on an order of magnitude well beyond the trajectory of business-as-usual. I will argue that these complex problems require addressing the epistemological error in knowledge systems reproducing unsustainable designed worlds.

Ecological literacy is a basis for nature-inspired design. Ecologically engaged knowledge must inform design strategies across the psychological, the social and the environmental domains. With the expansive three ecologies perspective, interventions at the intersection of design and economics can enable systems transitions. This theoretical work informs a framing of the current epoch in ways that create a foundation for the creation of regenerative, distributed and redirected design economies.

Enabling Difficult Confrontations for Intergeneration Solidarity and Survival

Presentation at the “Critical Pedagogies in the Neoliberal University: Expanding the Feminist Theme in the 21st century Art [and Design] School” session, #AAH2019 –Brighton, April 2019

Presentation at the “Critical Pedagogies in the Neoliberal University: Expanding the Feminist Theme in the 21st century Art [and Design] School” session, #AAH2019 –Brighton, April 2019

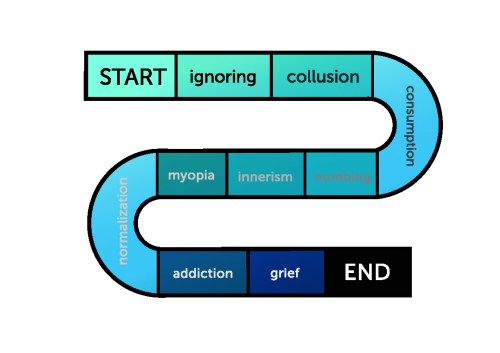

I will use this paper to reflect on tensions between generations of feminists with a focus on strategies of denial and their toll on the goals of feminist movements. Feminists movements have historically worked (with varying degrees of success) to end the normalisation of denial of social injustices and symbolic, structural and/or actual violence. Feminist pedagogy must intensify challenges to various manifestations of denial responsible for reproducing patriarchy, oppressive social relations and ecocide.

This paper will address denial in the face of divisive issues such as the ‘me too’ movement; the precarity faced by younger generations; and the intersections of patriarchy and ecological crises. It is based on my personal experience as a daughter of a feminist academic in Canada, as a student at art school and my current role as lecturer in design education oriented towards social and environmental justice. Solidarity and even survival depends on our ability to make confrontations with disturbing information a catalyst for change. The lessons learned from feminist struggles inform the work of confronting oppressions, including those on issues of environment justice.

https://www.slideshare.net/ecolabs/slideshelf

My experiences have led me to the conclusion that many, if not most, oppressive behaviours and attitudes are rooted in various types of denial and unconscious bias. Both are deep seated forces that prevent many of us (and especially those with more privilege) from seeing things that disturb our self-image. Feminist strategies such as transformative learning help us negotiate these difficult confrontations. These are needed now more than ever in higher education and beyond. Unfortunately, neoliberal modes of governance all but destroy opportunities for transformative learning.

Book talk at Cliffs, Margate, June 2018. Photo by Dave Elliot.

Book talk at Cliffs, Margate, June 2018. Photo by Dave Elliot.Within the Anthropocene, Beyond the Capitalocene, Towards the Ecocene

UPCOMING paper at

London Conference in Critical Thought

Politics of/in the Anthropocene 3 – Design for Entanglements

29-30 June 2018

University of Westminster

309 Regent Street

London, W1B 2HW

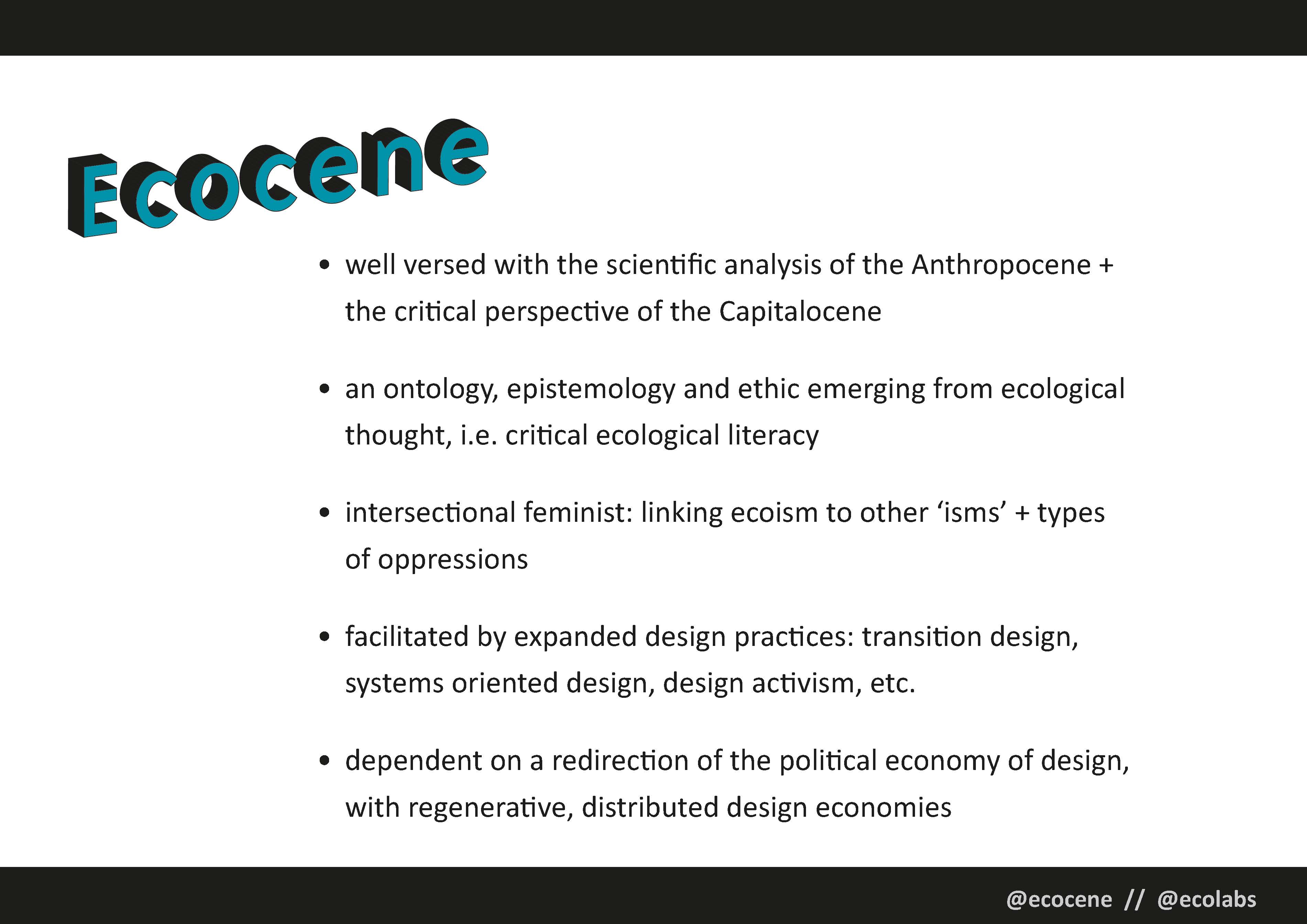

The global challenges of the Anthropocene demand shifts on an order of magnitude well beyond the trajectory of business-as-usual. Ecomodernists’ fantasies of technological salvation are unhelpful when they sideline work undoing the assumptions that created the conditions of the Anthropocene in the first place. Erroneous ideas are embedded in the cultural fabric: the laws, policies and practices that determine how we live and act upon our surrounding lifeworld. The inevitable contradictions are increasingly dysfunctional. The Capitalocene concept (Moore 2014) more helpfully highlights the specific socio-political dynamics that propel environmental crises. Yet there are limitations to this critical approach. While defining the problem, it is does less well envisioning viable alternatives. Ecological theorists Gregory Bateson and Felix Guattari offer a foundation for approaching these contradictions by thinking simultaneously about three interconnected domains: the self, the social and the ecological. Conjoining these three ecologies, this paper will describe the contours of an emergent ‘Ecocene’ (Boehnert 2018) as a generative alternative. Moving beyond the limitations of reductionist models of the human psyche and knowledge systems, design interventions must nurture relational perception and foster new sensibilities. As subjects opening inward, in participation with our surrounding lifeworlds, intersectional solidarity demands engaged encounters with oppressions that threaten collective futures. The Ecocene is a foundation for the redesign of the system structures that determine what is designed. Participant designers, well versed in ontological entanglements, are well poised to enable these emergent ways of seeing and knowing to make transitions to another world not only possible but desirable.

References

Bateson G (1972) Steps to an Ecology of Mind. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Boehnert J (2018) Design, Ecology, Politics: Towards the Ecocene. London: Bloomsbury.

Guattari F (2000/1989)The Three Ecologies. London: Continuum.

Moore J W (2014) ‘The Capitalocene. Part I: On the Nature & Origins of Our Ecological Crisis’. Accessed online.

Register for the free conference here.

Design/Ecology/Politics: Toward the Ecocene describes a role for design in making sustainable ways of living not only possible but desirable. This book examines the relationships between three domains. Part One ‘Design’ explains how new ways of living are created and made appealing. Part Two ‘Ecology’ explores the philosophical problems at the root of the environmental crisis and how design can either contribute to – or address these problems. Part Three ‘Politics’ describes why sustainable transitions are currently so difficult to achieve. By theorising design, ecological and socio-political theory concurrently, Boehnert describes how social relations are constructed, reproduced and obfuscated by design in ways which often cause environmental and social harms. Where design theory fails to recognise the historical roots of unsustainable practice, it reproduces old errors. With the understanding that design negotiates the intimately intertwined space between self, society and the environment, design can more effectively engage with complex contemporary challenges. The transformative potential of design is dependent on deep-reaching analysis of the problems design attempts to address. With this ecologically literate, critically engaged and intersectional feminist foundation, design is a practice primed to facilitate the creation of sustainable and just futures.

Design, Ecology, Politics: Toward the Ecocene has been published by Bloomsbury Academic February 8th, 2018. The book website is now live. The launch on Regents Street in London, February 9th, 2018.